If you’re like most people in the world today, it’s not what you thought…and it’s way more important than you thought.

Money is constantly being passed from person to person and place to place. We receive it from employers, clients, or other sources, and we use it to pay for groceries, gas, housing, clothing, etc. But where did it start? Where does the money we use come from originally? The answer to that depends on what kind of money it is. We actually have three main types of money used by the U.S. public, and they come from different sources.

In the US, coins are made at the US Mint and issued by the Treasury via our central bank, the Federal Reserve. Cash bills are printed by the Bureau of Printing and Engraving and issued (through a slightly convoluted process) by the Federal Reserve. But only a small fraction of the money used in our economy is bills or coins. Most of what are considered cash transactions are done with debit cards, checks, or electronic transfers—bank-account money. The money involved in these transactions is just account entries; no dollar bills or coins are involved. Most of the money both here and throughout the world is bank-account money, and it’s created by commercial banks when they make loans.

If that seems outrageous or less than credible to you, you’re not alone. This isn’t something that’s publicized or talked about a lot. But if we explore the facts and the principles of modern banking, I think you’ll see that it’s true.

“…the majority of money in the modern economy is created by commercial banks making loans.”

Money Creation in the Modern Economy Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1

How most people think banking works

What most people were taught about banking, if they were taught anything, is something like this:

- A bank takes in deposits from customers, keeps the money safe, and maintains accounts.

- The customers use the accounts to make or receive payments without having to use cash.

- The bank lends out a portion of the money their customers deposit, and keeps a fraction of it in reserve, so customers can withdraw the cash if they want to.

The name for the above system is Fractional Reserve Banking. The rationale behind it is that most people will leave the money in the bank most of the time. They can carry on transactions simply by transferring account entries from one account to another without using the actual cash money. The idea, as it’s ordinarily promoted, is that this is beneficial to the community because while the depositors aren’t using their money, someone else can be using it to expand a business or buy a house.

Traditionally the fraction required for reserves was 10%. The bank could lend out 90% of the money it had on deposit. The reserves are intended to cover the occasions when people with deposits want to take the money out of the bank. What’s called a “run on the bank” is when the amount of cash depositors are trying to withdraw is greater than the amount the bank has available.

The rest of the story

The classic 1946 movie, It’s a Wonderful Life, depicted part of the story of our banking system. When there’s a run on the savings and loan, George Bailey (played by Jimmy Stewart) tells his customers, “You’re thinking of this place all wrong, as if I had the money back in a safe. The money’s not here. Your money’s in Joe’s house—that’s right next to yours—and in the Kennedy house and Mrs. Menklin’s house and a hundred others.” This is how it’s ordinarily justified—you’re not using the money right now, so someone else can use it and everyone benefits.

However, the movie and most other depictions of the banking system are leaving out a big part of the story. In the movie, it’s strongly implied that all the depositors whose money isn’t in the safe anymore should stop whining because the money has been put to good use helping Mrs. Menklin buy a house. But let’s look at the backstory that isn’t included in the movie.

The implied story is that when Mrs. Menklin came in for a loan, George Baily took $5000 out of the safe (yes really $5000—it was 1946) and put it in a canvas banker’s bag and zipped it up and gave it to her, and she signed a contract agreeing to pay it back with interest. Mrs. Menklin took the bankers bag of money and gave it to Fred Johnson, who owned the house she wanted to buy, and Fred signed over the deed and gave her the keys. So that’s why the money isn’t in the safe—it’s so Mrs Menklin can live in a nice little house instead of a crummy apartment.

But…there’s another step. Fred Johnson has a canvas banker’s bag with $5000 in it. He doesn’t want to carry it around or leave it at home where he could be robbed, so he deposits it in George Bailey’s savings and loan…

George Baily hadn’t subtracted anything from anyone’s account when he took the money out of the safe, so all that money still exists as account entries in all those depositors’ accounts. But now another $5000 exists in Fred Johnson’s account. George Bailey’s savings and loan has just created $5000.

And not only that, the safe has been replenished. George can now take money out of the safe again and lend it to the Kennedys or whoever else is applying for a loan. This is the mechanism that provides the underlying principle for bank creation of money. There’s a name for it in monetary/economic circles, it’s called the money multiplier. (You can Google it.)

If the story doesn’t quite make it clear, following is a step by step explanation of the process with diagrams.

Money Creation in the It’s a Wonderful Life Model

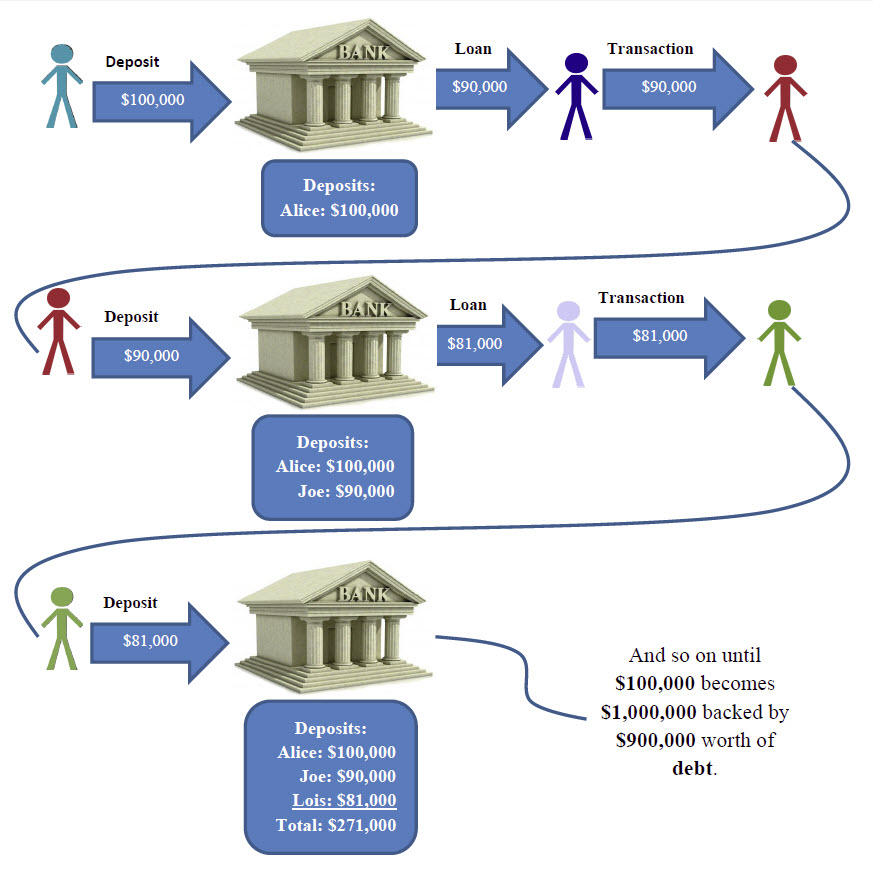

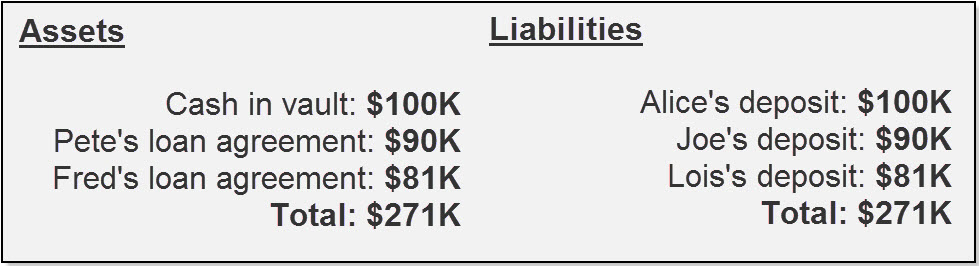

To demonstrate fractional reserve money, we’ll look at a simple theoretical example. We’ll lump all banks into one and just work with “the bank”. We start from zero and suppose that Alice comes into the bank and deposits $100,000 in currency. The bank now has $100,000 on deposit of which it can lend out 90% or $90,000.

The bank lends $90,000 to Pete. Pete pays the $90,000 to Joe for a boat, and Joe, rather than carrying $90,000 around in a briefcase or putting it under his mattress, deposits it in the bank.

At this point the bank has $190,000 in deposits, and it considers the new deposit brand new money. Therefore, it’s free to lend out 90% of this new deposit. It now lends $81,000 to Fred, which Fred pays to Lois for design and decorating services for his business office. Lois, of course, deposits the $81,000 in the bank. Once again, the bank considers it has brand new, fresh, debt-free money on deposit. Now we have:

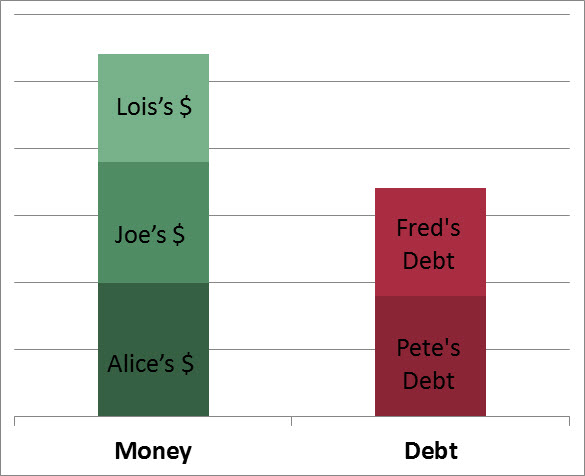

$100,000 Alice

$90,000 Joe

$81,000 Lois

$271,000 Total

By these three steps, the money supply has gone from $100,000 to $271,000. Note that Alice, Joe, and Lois all consider the money they have on account is their own money with no strings or debts attached. Pete and Fred may be making or not making monthly payments on their debts, but with regard to Joe’s and Lois’s deposits, that’s no concern of the bank and no concern of the account holders. As far as they’re concerned, that money is real money, free and clear.

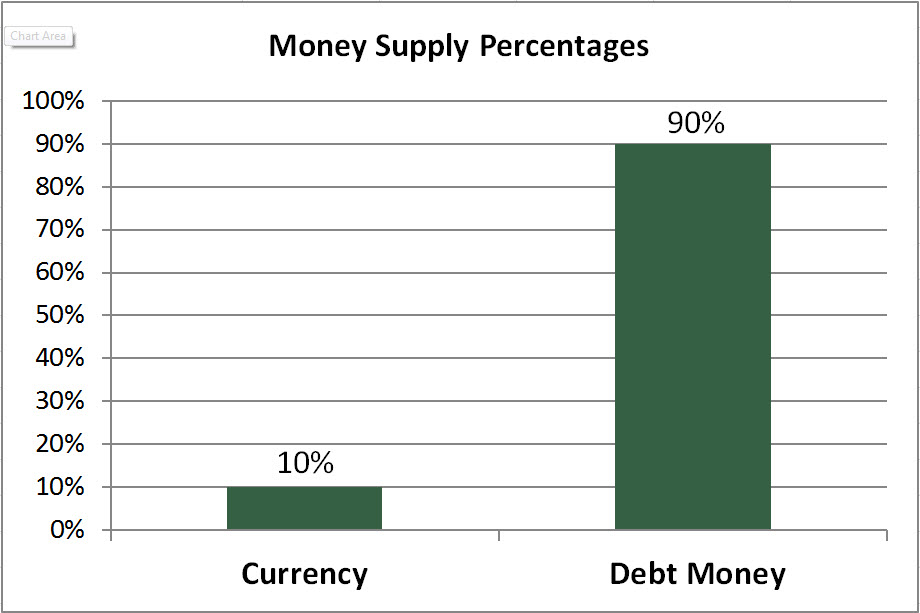

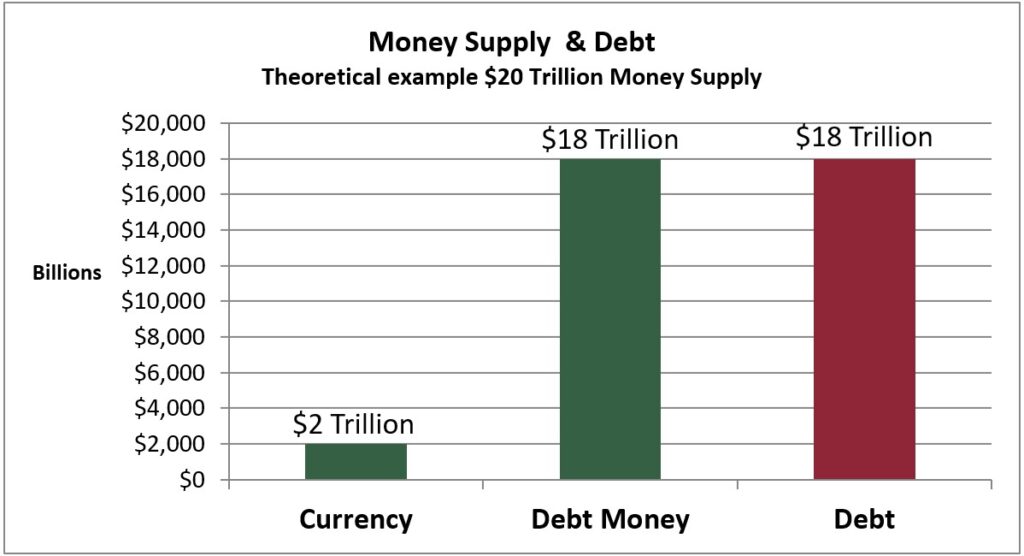

If you continue this process until the re-deposited amount gets down to near zero, eventually $100,000 currency turns into about $1,000,000. The process creates $900,000 of debt-based money out of $100,000 currency. Thus we’d get a money supply that was 90% debt-based and 10% currency.

If we assign actual numbers and include the debt on the graph, our system would look something like this:

The description above is based on the traditional story of fractional reserve banking to show how its basic principles allow banks to create money. This isn’t what banks actually do.

What the Banks are Really Doing—It’s a wonderful life at the bank

In modern times particularly, there are a couple of major differences between the It’s a Wonderful Life story and reality.

The biggest difference is that when a bank makes a loan, they don’t generally give the borrower cash. They write a check or make an account entry. Bank-account money. It works a little different than cash.

If there’s a 10% reserve requirement, it means the banks have to maintain reserves equal to 10% of their customer deposits. The reserves can be either cash in their vault or money in their reserve account with the central bank. So, in the It’s a Wonderful Life money-creation scenario described above, when Alice comes into the bank with her $100,000 cash, the bank makes an account entry that Alice has $100,000 on deposit, and they put $100,000 cash in the vault.

Now…they could look at this on the basis that they have to hold onto at least $10,000 of that cash to cover the reserves for Alice’s deposit, and they’re free to lend out the rest. But they could also look at it another way. They have $100,000 cash in the vault, which is 10% of what? — a million dollars. And they only have $100,000 on deposit. Therefore, they now have room for another $900,000 in deposits to still be within their reserve requirement. And they can create those deposits by making loans. This is how they look at it.

So in the simplified It’s a Wonderful Life money-creation example above, what they’d do is just plunk the $100,000 cash in the vault and start making loans till they reached $900,000. They don’t send the cash out the door and then wait for Joe and Lois to trundle back into the bank with briefcases full of cash. When they lend the $90,000 to Pete to pay to Joe for a boat, they just cut right to the chase and make a deposit entry in Joe’s account.

“The actual process of money creation takes place primarily in banks. …checkable liabilities of banks are money. These liabilities are customers’ accounts. They increase when customers deposit currency and checks and when the proceeds of loans made by the banks are credited to borrowers’ accounts.”

Modern Money Mechanics,

Booklet published by the Chicago Federal Reserve bank 1994

As strange and outrageous as this may seem if you weren’t previously aware of it, this is how most of our money is created. It works, to the degree that it does, because commercial banks are in a unique position not shared by any other type of corporation or organization. The bank-account balances that you and I are passing back and forth as we make exchanges, are liabilities on the banks’ balance sheets—bank IOUs. As the holders of deposit accounts, they’re issuing IOUs that the entire economy is using as money. That is the thing that puts them in a position to create money by making balance sheet entries.

Balance Sheets

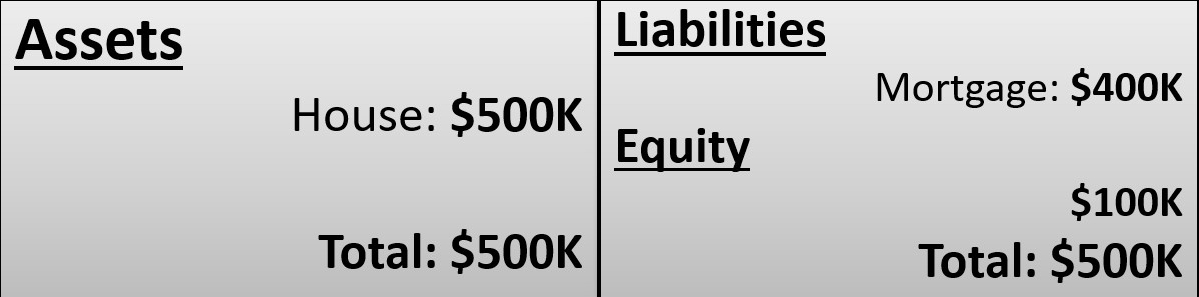

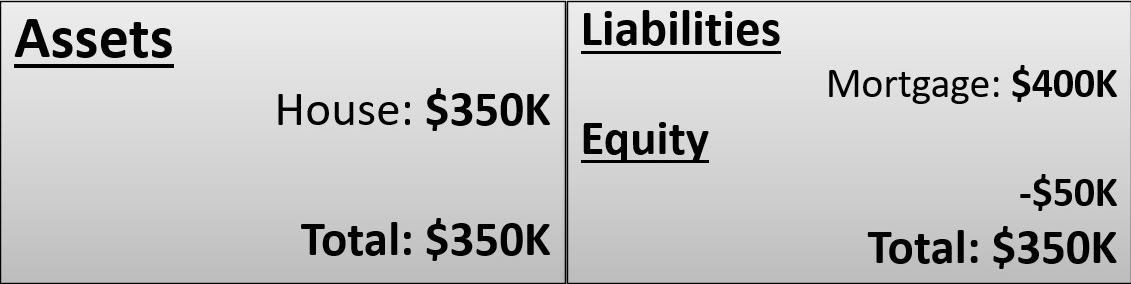

If you are unfamiliar with balance sheets, the essence is this:

It has two sides with Assets on the left side and Liabilities and Equity on the right side. Assets are valuables that you have in your possession whether you owe money on them or not. Liabilities are debts, and Equity is the value of what you own free and clear. The two sides add up to the same amount. The worth of your assets is equal to the amount of money you owe plus the value of what you own without obligation.

For example, if you buy a $500K house with a $100k down payment and a $400K mortgage, your home-owner balance sheet would look something like this.

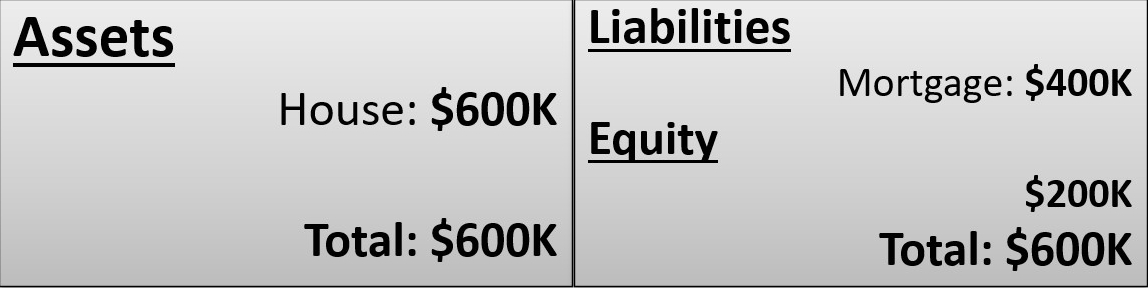

If the value of your house goes up and you don’t borrow any additional money against it, then the value of your equity goes up correspondingly. If the house is now worth $600K and the mortgage is still $400K, your equity would be $200K.

Likewise if the value of the house goes down, your equity is reduced. If the house value dropped below $400K then your equity would become negative. The balance sheet always balances.

So back to the banks, the way they create money and keep their balance sheet balanced is by issuing their IOUs in exchange for borrowers’ IOUs. If you get a mortgage loan from a bank, the promissory note that you sign agreeing to pay back principal plus interest is an asset for the bank–a promise of future money. The account entry that the bank makes creating the principal proceeds of the loan is a liability for them, their IOU. The trick of it being that their IOUs happen to be what the rest of us are using as money—thus, they are creating money.

The section of their balance sheet for our imaginary scenario above would look like this:

The evolution that put them in a position to legally do this comes from the core principles of fractional reserve banking, just as it’s described in the It’s a Wonderful Life model. As soon as we say that George Bailey is allowed to take the depositors’ money out of the safe and lend it to Joe and Mrs. Menklin to buy their houses, we’ve given the banks the power to create money. All they’ve done when they create deposits out of nothing is the logical, efficient streamlining of the process.

Real World

The above examples are very simplified of course. In reality it’s more complicated, particularly since we don’t all use the same bank. There are many different commercial banks, which are overseen and coordinated by our central bank, the Federal Reserve. A person may have their deposit account at one bank, get a mortgage loan from another bank, and have the proceeds paid to a house seller with an account at a third bank. Though the process is more complicated than the descriptions above, the operating principles and the effects on the overall system and the money supply for the economy are the same.

Another real-world difference worth noting is that starting in March 2020, the reserve requirement in the US is zero percent. The reason given for the change had to do with a build-up of excess bank reserves that had resulted from the Federal Reserve’s efforts to boost the economy after the crash of ’08 and during the Covid pandemic. Banks do still have reserves (as of January 2023, there is still a large excess of bank reserves in the system overall). They need to have a certain amount of reserves in their accounts at the Federal Reserve bank, since they use funds in those reserve accounts for settling transactions between banks.

Also worth noting is that even back when there was a reserve requirement, it wasn’t acting as a significant restraint to bank lending and money creation. If a bank’s lending exceeded their required reserve ratio, they would make up the difference in their reserve account by borrowing from another bank that had excess reserves or by borrowing from the Federal Reserve bank.

Why banks can go bankrupt

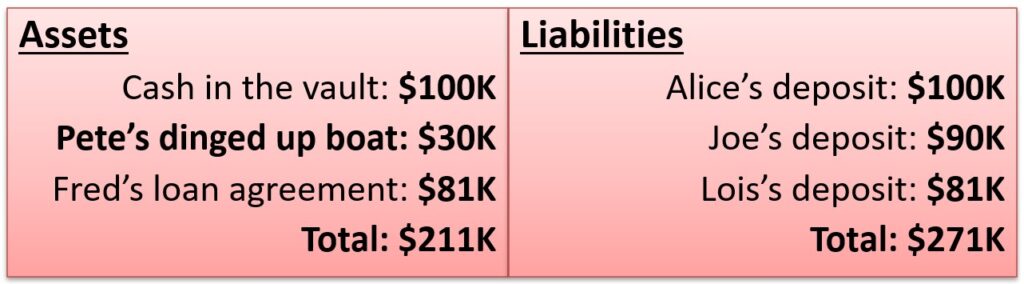

You might think an entity that can create money couldn’t possibly go bankrupt. The reason they can, comes back to the fact that the created money is a liability, and the assets that are balancing against their liabilities are mostly loan agreements from borrowers. Continuing our little scenario from above, if Pete defaults on his loan and the bank has to repossess a dinged-up barnacle-encrusted boat, that portion of their balance sheet might look like this:

This is not a good thing for the bank.

The bank, of course, has some of its own cash or other assets against which there are no liabilities—the Equity on their balance sheet. As long as their total assets are still greater than their total liabilities they can absorb a few defaults and still be considered balanced or sound.

But if a lot of their assets start abruptly losing value because of defaults, they can get into a situation where their total assets are less than their total liabilities. They have more debt than they could possibly pay, which is to say they’re insolvent. This is the point where they get swallowed by Morgan Chase or bailed out by the government.

Core Problems

As no doubt you can see, there are problems with creating money in this way. Besides the instability of relying on circular IOUs, it requires people to be in debt in order for the economy to have any money. In fact, it requires a whole lot of people to be in a lot of debt all the time. And pay interest on it.

Just like money is created when a bank makes a loan, money disappears when the loan is repaid. Recall that the money the bank creates is just its own IOU to the depositor. When you pay back the principal on a mortgage loan, you now have less debt, and the bank, rather than having more money also has less debt. The money you pay for interest is income for the bank, and it can come back into public circulation when the bank spends it, but the money paid on principal is gone; it’s no longer money. In our current system, the only thing that will create new money to replenish the supply is someone somewhere borrowing more money from a bank. We have to have constant borrowing just to keep the money supply from diminishing. Any slow-down in borrowing will translate to less money.

For more on this and the many other negative ramifications of this form of money creation, see How the Debt-Based Money System Works (and doesn’t work).

References

Money Creation in the Modern Economy Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1

Money in the Modern Economy, an Introduction Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1

Commercial Banks as Creators of Money James Tobin, July 24, 1963

Modern Money Mechanics, Booklet published by the Chicago Federal Reserve bank and made publicly available between 1968 and 1994, republished as a free download by Wikisource. Also available through Internet Archive.

Last updated: July 12, 2022

Photo credit: Money tree jgroup / 123RF Stock